Why Practice Doesn’t Necessarily Make Perfect

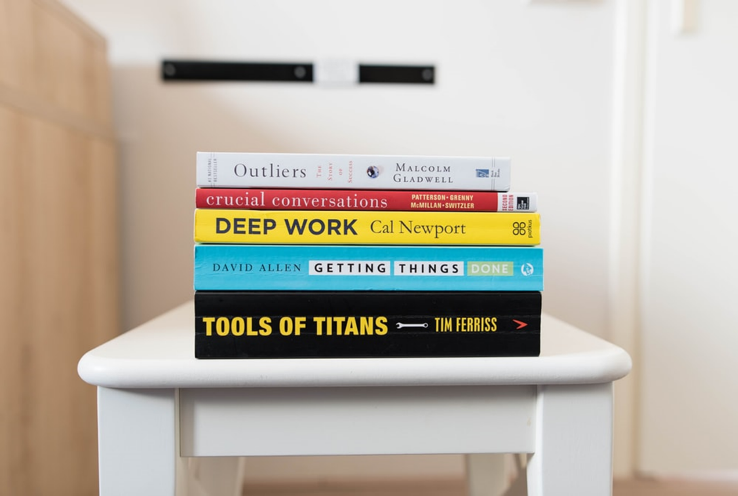

Ever since the publication in 2008 of Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, controversy has raged about one of the author’s main claims – that to become truly an expert in any field, one must practice for a minimum of 10,000 hours and, ideally, to have reached this point by the age of 20. Many critics have focused on Gladwell’s habit of cherry-picking convenient facts and stats, and a good example is his theory concerning The Beatles.

His assertion was that the group would never have been able to scale such heights of musical ability so young if they had never spent several months playing in Hamburg clubs. Often having to play two or three sets a night, seven days a week, this gave Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr the opportunity to put in many more hours than if they had stayed in Liverpool playing at weekends with the occasional midweek performance too.

Another example used by Gladwell was that of Bill Gates. He claimed that, by being able to use a school computer from the age of 13 onwards, the billionaire was able to rack up 10,000 hours of programming experience before getting to university, giving him a huge advantage over most of his peers.

Some reviewers of the book found that the 10,000 hours theory was perhaps just a little too neat an explanation and that other factors could be just as important. For example, success in fields as diverse as sports and music also has a great deal to do with an individual’s interest in the activity, not to mention a genetic aptitude too.

The difference between good and great

One researcher, in particular, who has worked hard to debunk the 10,000 hours’ practice theory is Brooke Macnamara, an academic at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. Along with her colleague, Megha Maitra, Macnamara decided to focus on violinists for her study. In the project, 13 players of the instrument were interviewed and who had been put into three groups of having the best, good, and simply proficient musical skills. In carrying out in-depth research, it emerged that the latter group had probably spent fewer hours practicing than the others – an average of 6,000 hours up to the age of 20. But the good and the best players had notched up almost identical totals at around 11,000 hours each. So there was some other factor that separated the two groups,

One researcher, in particular, who has worked hard to debunk the 10,000 hours’ practice theory is Brooke Macnamara, an academic at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. Along with her colleague, Megha Maitra, Macnamara decided to focus on violinists for her study. In the project, 13 players of the instrument were interviewed and who had been put into three groups of having the best, good, and simply proficient musical skills. In carrying out in-depth research, it emerged that the latter group had probably spent fewer hours practicing than the others – an average of 6,000 hours up to the age of 20. But the good and the best players had notched up almost identical totals at around 11,000 hours each. So there was some other factor that separated the two groups,

One particular aspect that Macnamara believes is critical for reaching the highest levels in any activity is having a genuine passion for it. This is by no means a new revelation. It is commonly also seen as a prerequisite for success in any field passion, from becoming an expert sportsperson to choosing successful ways to invest.

But practice does matter

Of course, this doesn’t negate the need for practice. This is why, when taking the presumably complex skill of investing as an example, many people new to the activity choose to gain a few of the initial skills using so-called demo accounts. This is especially useful for those hoping to start forex trading, as it allows them to learn the ins and outs of the activity. There are even online guides to help find the most suitable demo account, which can direct newcomers to the different trading platforms available.

The relief for people planning to pick up this skill, or any other, is that it does now seem like the requirement to spend the equivalent of around 14 months of our lives to perfect it is not necessarily true.

In fact, it as much relies on our enthusiasm for the task in hand as well as a few genetic and environmental factors too.